Home › Sea Wildlife › Marine Species › Vertebrates › Remora

Interesting Facts about Remoras

[Remora Phylum: Chordata] [Class: Actinopterygii] [Order: Carangiformes] [Family: Echeneidae]

Some divers call them 'suckerfish' and others use the term 'sharksuckers'. No matter which, remoras have several unique adaptations that help differentiate them from other marine species.

This section contains some fascinating facts about remora (Echeneidae), such as where they are found, what they eat, and how these ray-finned pelagic suckerfish reproduce.

Suckerfish Geographic Range and Habitats

Worldwide, sharksuckers have a widespread distribution in almost all tropical and subtropical oceans.

You can find remoras in most warm water environments, especially:

- Atlantic Ocean (e.g., the Caribbean Sea, Bahamas, and Bermuda)

- Gulf of Mexico (including Belize, Cuba, and the Yucatan Peninsula)

- Indian Ocean (Australia, India, Mauritius, and Réunion)

- Pacific Ocean (Central America, Costa Rica, and El Salvador)

- The Red Sea Basin (rift between Africa and the Arabian Peninsula)

In general, remoras are a pelagic species, meaning they live offshore in the open ocean. However, depending on the chosen habitat of their host species, of which there are many, it's not unusual to see them in shallow coastal zones - or even swimming freely at the surface.

As a result, they need to tolerate a variety of depth ranges, especially if they are attached to a host that likes to dive deep.

But for the most part, remora fish live between sea level and down to about one hundred (100) metres (330 feet).

What Animals Do Remora Attach to?

Remoras use their sucker disk, the flat and modified oval shaped dorsal fin located on top of their head, to attach themselves to the body of other creatures.

The special suction disc helps these marine "hitchhikers" get free transportation, increased protection, and access to the host's discarded food scraps or ectoparasites that live on gills and fins (such as fish lice and isopods).

Some of the marine animals that suckerfish attach themselves to include:

- Large rays (especially manta rays)

- Large bony fishes (e.g., groupers, marlins, and ocean sunfish)

- Marine mammals (dolphins, dugongs, and whales)

- Sharks (especially):

- bull sharks (Carcharhinus leucas)

- Caribbean reef sharks (Carcharhinus perezi)

- lemon sharks (Negaprion brevirostris)

- oceanic whitetip sharks (Carcharhinus longimanus)

- tiger sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier)

- whale sharks (Rhincodon typus)

- zebra sharks (Stegostoma tigrinum)

- Sea turtles (especially):

- green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas)

- leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea)

- loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta)

- olive ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea)

- Ship hulls (the Latin translation of the term remora is "delay" which is a historical reference to the "hindrance" or "drag" caused by sharksuckers attached to ships)

Fun Fact: If you're wondering... Can a remora attach to a human, such as a scuba diver, and can it bite you? Yes, their strong suction abilities have been experienced by many scuba divers (including myself at some Thailand dive sites) though the suckerfish does not cause any significant harm to humans.

Remora Suckerfish Characteristics

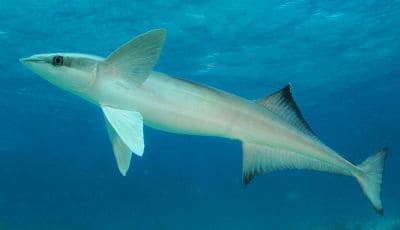

The remora is a long, thin fish with a slate-gray body. There are several unique adaptations and behavioural traits that set them apart from other marine species.

Remora Suction Cup (Modified Dorsal Fin)

In fact the flattened oval suction disc on top of the head evolved from the first dorsal fin. The pectinated lamellae (parallel bony plates with teeth-like spinules) create suction when the fish presses itself against a smooth surface and tilts its body backward.

This mechanism means a remora can attach its head firmly to another fish (or animal) without causing them any harm whatsoever, even a fast-swimming dolphin or shark. When the remora swims forward, it breaks the seal and it becomes instantly detached.

A Commensal Relationship with Phoresy

In general, the commensalism exhibited between remoras and their hosts is of more benefit to the small fish than the host.

Even so, it is a mutualistic behaviour that can reduce parasite loads on some of the biggest carriers, such as blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus).

What Do Suckerfish Eat?

What Do Suckerfish Eat?

- A host's parasites and dead skin (same as cleaner fish at cleaning stations)

- Filtered planktonic material (including free-swimming organisms and small fish fry)

- Leftover food scraps (such as those discarded by manta rays and sharks)

Fast and Streamlined Swimmers

When they're not attached, suckerfish are fast and extremely agile swimmers. Their body is tapered and they have long pectoral fins for efficient maneuvering. Plus, having a flattened head and smooth skin helps to reduce drag.

Unique Anatomy and Physiology

It is true that remoras spend most of their life cycle attached to other animals. Even so, they have fully functional swim bladders and they are capable of detaching themselves to swim freely and independently.

Interesting Fact: Some elongate fish are similar to remoras. For example, scientists believe they may be closely related to the cobia fish (Rachycentron canadum) and the dolphinfish (Mahi Mahi).

Different Types of Remora Fish

Common Remora (Remora remora)

Marlin Sucker (Remora osteochir)

Saddleback Remora (Remora ostrich)

Slender Sharksucker (Phtheirichthys lineatus)

The longest remora is the live sharksucker (Echeneis naucrates), also called the slender suckerfish, which can grow up to 110 centimetres (43 inches) in total body length.

Spearfish Remora (Remora brachyptera)

Striped Remora (Echeneis naucrates)

Whalesucker (Remora australis)

White Suckerfish (Remora albescens)

The white remora (Remora albescens) is one of the shortest and they rarely grow longer than thirty (30) centimetres (12 inches).

How Do Sharksuckers Reproduce?

In general, remoras need to be at least thirty centimetres long before they attain sexual maturity. It's difficult to distinguish the sexes by appearance, but mature males tend to have longer pelvic fins.

Like many large bony fish species, remoras also reproduce sexually and they're oviparous, meaning they lay eggs.

External fertilisation occurs when males and females release sperm and eggs into the open water (an event known as 'broadcast spawning').

So, because parental care is nonexistent, the eggs and larvae are left to drift freely with other kinds of planktonic organisms.

Spawning and Larval Stage

General research observations suggest that spawning takes place when the surface waters are warmer, such as when plankton conditions are favourable.

Remora eggs are tiny and buoyant. While they float in the water column, they are completely free-swimming and do not attach to any hosts.

As they grow, the suction cup starts to develop as an adaptation of the first dorsal. This is when juvenile suckerfish start associating themselves with floating debris or small animals, such as marine rays and sea turtles.

Interesting Fact: Because remoras often stick to migratory animals for most of their life, the gene flow is quite high across oceanic basins. In other words, their hosts are transporting them to unfamiliar regions to spawn and mix genetics.

Suckerfish Predators and Threats

The lifespan of remora species ranges between two (2) and eight (8) years. Yes, they are efficient hitchhikers, but they're certainly not immune to danger in the oceans.

In the wild, the main predators of suckerfish are:

- Amberjacks (Seriola)

- Barracudas

- Cephalopods (especially large squids)

- Groupers

- Marine mammals

- Seabirds

- Sharks (mostly when unattached)

- Tuna

They are not the most targeted of marine vertebrates by humans, but they still face a number of indirect threats from certain kinds of human activities, including:

- Ocean acidification

- Habitat destruction

- Coral reef destruction

- Overfishing

- Plastic pollution

Important: The monitoring of suckerfish populations is poor, and some of the major declines in shark and ray species may impact their long term survival rates. However, the IUCN Red List shows the conservation status of remoras as "Least Concern" (LC).

Related Information and Help Guides

- Lizardfish Facts and Species Information with Pictures

- Interesting Facts about Jawfishes (Opistognathidae)

- What Kind of Fish is Sea Bream and What Do They Eat?

Note: The short video [2:09 minutes] presented by 'Deep Marine Scenes' contains more remora fish facts with footage of how they attach to sharks and other marine animals.