Home › Sea Wildlife › Marine › Invertebrate › Crustaceans › Shrimp › Anatomy

Interesting Facts about Shrimp Body Parts

The biological structures of shrimps are an ideal match for a ten-legged decapod crustacean that thrives in various types of aquatic environments.

This page explains how the internal and external anatomical features of sea shrimps work, with extra details about some special adaptations for life on the ocean floor.

What are the Basic Parts of Shrimp's Body?

Along with crabs and lobsters, shrimps are members of a group known as Malacostraca.

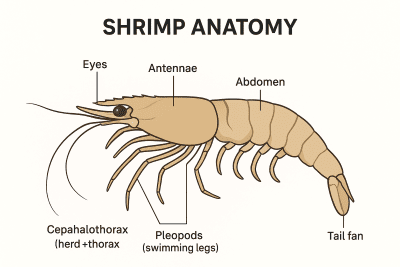

For simplicity, we can divide the segmented body structure of a shrimp into three main parts:

- Tail (the tail fan combines the telson and uropods for swimming)

- Abdomen (the pleon with 6 segments)

- Cephalothorax (fused head and thorax region covered by a protective shell - called a carapace)

The exoskeleton is made of a hard substance, called chitin. It is strong enough to support and protect the shrimp's internal organs, even though it will molt so they can grow. Shedding of the exoskeleton usually occurs every three weeks in adults.

Sea Shrimp Anatomy: External

Even though the abdomen is segmented, it also needs to be flexible. The "rostrum", situated above the eyes, is a rigid extension of the carapace that points forward to help protect the delicate ommatidia (compound eyes).

Shrimp eyes have adapted to detect movement and light in water, and they also provide them with a wide field of vision.

In fact, scientists think that the mantis shrimp (order Stomatopoda) has the most powerful eyes of any creature in the entire animal kingdom.

Shrimp Antennae and Antennules

The antennules are the shorter pair, and mostly used for balance and for detecting chemicals (a process known as chemoreception).

Whereas, the longest pair (antennae) are the most sensitive. Shrimps use them for touch, for gathering physical cues, and for sensing their way around their environment.

Mouthparts of a Shrimp

Other than the cleaner shrimps, most of the species are omnivores that eat algae and other types of planktonic material.

When feeding, some species use "hammer-like" mandibles (called dactyl clubs) to crush any food that has a hard shell. They also use maxillae and maxillipeds to manipulate and process their food.

The Walking Legs of a Shrimp

The order Decapoda refers to the fact that shrimps have five (5) pairs of walking legs (called pereiopods). It's also common for the first few pairs of legs to have claws (chelipeds) - mainly used as a defencive mechanism - and the remaining legs help with locomotion.

The pleopods are small paddle-like appendages (also called swimmerets) located underneath the abdomen and used for swimming.

The pleopods are small paddle-like appendages (also called swimmerets) located underneath the abdomen and used for swimming.

During sea shrimp reproduction, females use the pleopods to carry the brooding eggs.

The tail fan is formed by uropods and the telson - a central plate flanked by the rudder-like uropods.

This combination is an important feature that enables rapid movement. Thus, shrimps are able to generate a backward swimming "tail-flip escape" from natural predators, such as octopuses and a multitude of marine fishes.

Interesting Fact: The giant tiger prawn (Penaeus monodon) is one of the biggest of all shrimp species and often used commercially as a food source for humans. Fully grown adults can measure up to thirty three centimetres long (13 inches).

Sea Shrimp Anatomy: Internal

The digestion of food begins in the mouth. It enters the short esophagus before it moves down to the midgut and the hindgut.

After reaching the anterior and posterior stomach chambers, the grinding gastric mill goes to work to break down the food "mechanically".

The digestive gland (called the hepatopancreas) secretes enzymes and absorbs nutrients. The process ends with expulsion at the anus - located at the end of the telson.

Shrimp Circulatory System

The open circulatory system means the tissues receive fluid from the arteries in the form of a blood equivalent, a substance called hemolymph (often a blue-green colour).

Even though the heart of a shrimp is not inside its head, it sits closely behind the head and thorax for maximum protection.

Shrimp Respiratory System

There's very little room for the gills inside the branchial chamber situated beneath the carapace. However, specific movements of the maxillipeds facilitate sufficient ventilation by extracting oxygen from the water.

So, do shrimp have a brain?

Yes they do have a tiny brain. A collection of ventral nerve cords and miniature brain (supraesophageal ganglion) control sensory and motor functions, with segment-specific activities coordinated by ganglia.

What's the grey vein in shrimp?

It has many common names, but the scientific name for the dark line that runs through the back of a shrimp is the intestinal tract.

In actual fact, the vein is not a blood vessel, even though that's what it looks like. Instead, it contains the shrimp's waste products, which may also include sand and grit.

Special Anatomical Adaptations

The reproductive system of the male shrimp is made up with sperm housed in a petasma, testes, vasa deferentia, and the gonopods (copulatory appendages).

In contrast, females have ovaries and tubular shaped oviducts. She carries the eggs on her swimmerets (pleopods) until they hatch.

The male transfers spermatophores to the body of the female during mating. Hence, fertilisation of the egg cells occurs externally in shrimps.

Pro Tip: So, how long do shrimp live? Sea shrimp often lead a solitary lifestyle, and even though they form large schools during the spawning season, they rarely live for much longer than seven (7) years.